The Island's Antiquities Broker: Petros Kolokasides

Alexis Drakopoulos

Alexis Drakopoulos is a Greek Cypriot Machine Learning Engineer working in Financial Crimes. He is passionate about Archeology and making it accessible to everyone. About Me.

Who was Petros Kolokasides, and how did he shape the fate of Cyprus's ancient artifacts during the colonial era? This article analyzes his dealings within the framework of the 1935 Antiquities Law, highlighting the controversial export of heritage and the loss of vital historical information.

March 30, 2025

History

The story of Cyprus's cultural heritage is intertwined with periods of intense archaeological discovery and, often controversially, the subsequent dispersal of its ancient artifacts across the globe. Central to understanding the movement of antiquities during a significant portion of the British colonial era is the 1935 Antiquities Law. Replacing an earlier 1905 statute, this comprehensive legislation aimed to regulate the discovery, excavation, trade, and export of Cyprus's historical treasures, defined broadly as any object modified by human agency before 1700 AD. While intended to bring order and control, the law inadvertently formalized a market that saw countless items leave the island, often stripped of their crucial archaeological context.

The 1935 Law established a framework under the authority of a Director of Antiquities. It declared undiscovered antiquities the property of the Government and set procedures for accidental finds, requiring discoverers to report and deliver items to local authorities or the museum. The Director had the first option to acquire such finds for the Cyprus Museum, offering fair market value, with provisions for arbitration if the value was disputed. Only if the Director and the British Museum declined acquisition could the finder receive a permit to keep or dispose of the item. Crucially, the law mandated licenses for both archaeological excavation and for dealing in antiquities. It also stipulated that no antiquity could be exported without a specific license from the Director, who held the power to prohibit the export of items deemed essential to the public interest. Penalties, including fines and imprisonment, were prescribed for violations like illicit excavation or unlicensed export.

This structured, albeit colonial, approach to managing antiquities created an environment where licensed dealers could operate legally, sourcing artifacts from permitted excavations, accidental discoveries relinquished by the authorities, or existing collections. Within this context, several dealers established themselves. Among the most notable, yet persistently enigmatic, was a figure known as Petros Kolokasides, operating primarily in Nicosia from the early 1930s through to the 1960s. Despite the frequency with which his name appears in the provenance records of museums and private collections worldwide, biographical details remain scant. Critically, his name often marks the beginning of an object's documented history, with crucial information about the original findspot frequently missing, effectively erasing the archaeological context necessary for proper study. This paints a picture of a man deeply embedded in the island's antiquities trade but operating in a way that obscured origins and ultimately hindered future research.

Kolokasides presented himself through his business stationery as a dealer not just in antiquities but also in Persian rugs, suggesting a potentially diverse enterprise catering to colonial officers, travellers, and burgeoning international collectors – both institutional and private. His known Nicosia addresses were 3, Onassagoras Street and 42, Hippocrates Street, placing him centrally within the commercial heart of the capital during that era. These addresses served as nodes in a network that channelled Cypriot history, disconnected from its roots, out into the wider world.

The reach of Kolokasides's dealings was truly international, demonstrating the global demand for Cypriot artifacts during this period. Records show his sales reached institutions and, significantly, numerous private individuals far from Cyprus's shores. One documented destination was Australia, evidenced by receipts detailing transactions. These documents, often accompanied by lists or photographs of the objects, provide tangible proof of his activities and the types of artifacts passing through his hands, though rarely shedding light on their original context.

The objects themselves, sometimes itemized or pictured alongside the transaction records, included the pottery characteristic of various Cypriot archaeological periods – forms ranging from the early Bronze Age through to the Roman era. While valued for their historical significance and aesthetic qualities, their scientific value was often diminished by the lack of associated findspot data, a common issue with objects passing through the market at this time, including those handled by Kolokasides. These pieces were sought after by museums building collections, but also by private individuals, further dispersing Cyprus's heritage outside the public domain.

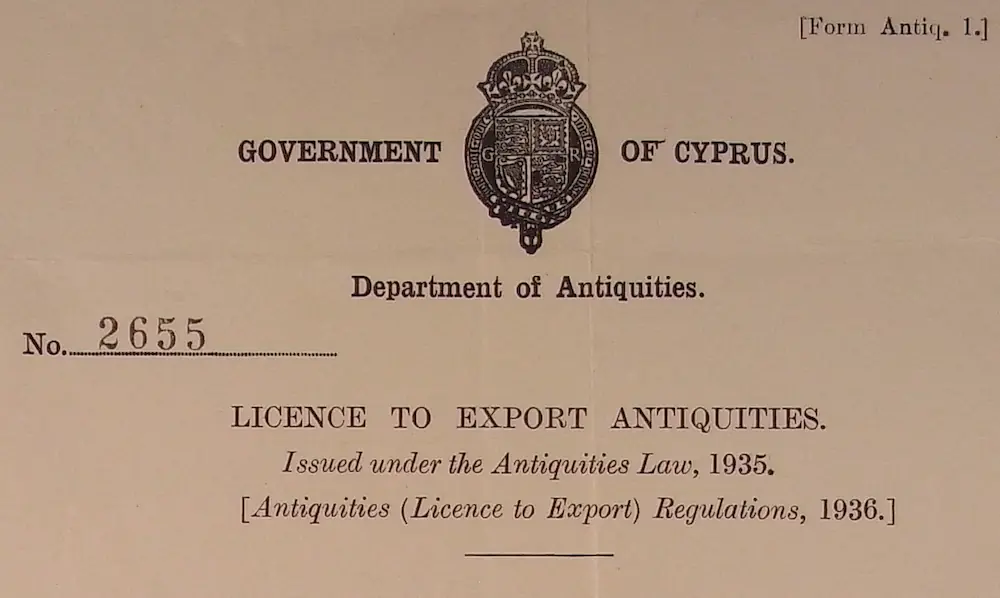

Each receipt represents a moment where Cypriot heritage was legally commodified and prepared for export under the provisions of the 1935 Law. Kolokasides, as a licensed dealer, would have navigated the requirements for obtaining export permits from the Director of Antiquities. However, the legality of the export did little to mitigate the loss of archaeological context. Furthermore, Kolokasides's practice of sometimes listing himself as the exporter on licenses obtained for his clients created significant administrative confusion. This obscured the identity of the actual owner/exporter in official records, making it extremely difficult, even today, for authorities like the Department of Antiquities to match specific objects abroad with their corresponding legal export documentation.

The paper trail left by Kolokasides extends across continents, including significant acquisitions by institutions and private collectors in the United States. Museums, universities, and private individuals in the USA became major recipients of antiquities from the Mediterranean and Near East during the mid-20th century. Kolokasides was a key supplier, channelling a considerable volume of Cypriot material into these collections, often without accompanying archaeological data.

A notable example is the presence of objects sourced from Kolokasides within the collections of prestigious American universities, such as Harvard. The journey of an artifact, like the terracotta figure depicted, from its discovery (often unrecorded) in Cyprus to its arrival in a museum gallery or private home frequently involved dealers like Kolokasides. While his role as an intermediary is documented, this documentation often marks a dead end for tracing the object's origins. These objects, once part of a sanctuary or tomb, became isolated data points in an international market operating under the ambiguous protections of the 1935 Antiquities Law.

The provenance – the documented history of ownership and origin – is vital, yet often frustratingly incomplete for items handled by Kolokasides. Museum records list him as the source, noting the year of purchase, but this frequently represents the earliest known point in the object's history outside Cyprus. This figurine from Harvard's Museum, for instance, names "P. Kolokasides, Nicosia, Cyprus" in its acquisition history (1953), but its pre-Kolokasides life, including where and how it was found, remains unknown.

Academic publications and museum catalogues further cement Kolokasides's role but also highlight the problem. References cite him directly, listing objects acquired from him – often pottery, terracotta figurines, and limestone sculpture. While building a picture of his activity, these references simultaneously underscore the vast quantities of archaeological material that entered collections via his dealership lacking essential contextual information.

While the 1935 law required dealers to be licensed and necessitated applications for export licenses, the degree to which dealers' sources and full inventories were scrutinized remains unclear. The fact that so many objects handled by Kolokasides lack findspots suggests that the system provided loopholes or that enforcement regarding provenance documentation was lax. Whether his sources were limited to legitimate excavations and chance finds processed according to law, or also included materials from undocumented or illicit digging, is a crucial question clouded by the passage of time and the nature of the trade itself.

The Legacy of the 1935 Law and Kolokasides's Era

The 1935 Antiquities Law represented the colonial administration's attempt to systematize the handling of Cyprus's past. It established the Cyprus Museum, created mechanisms for controlling excavation and export, and asserted government ownership over undiscovered finds. It aimed to preserve key sites ("ancient monuments" ) and ensure a share of excavated artifacts remained on the island, particularly those needed for the "scientific complement of the Museum".

However, the practical application and consequences of the law were complex and, in many ways, detrimental to the holistic preservation of Cypriot heritage. By licensing dealers and permitting export, the law facilitated a regulated, yet extensive, outflow of artifacts, often prioritizing the object itself over its invaluable archaeological context. Figures like P. Kolokasides operated effectively within this system. His activities highlight several critical issues:

- Loss of Archaeological Context: A significant portion of the material that passed through his hands lacks findspot data, rendering the objects almost useless for rigorous archaeological analysis and severing their connection to the specific historical and cultural landscape of Cyprus.

- Dispersal into Private Hands: Kolokasides sold extensively not only to museums but also to private collectors worldwide, scattering Cyprus's heritage into contexts where public access and long-term preservation are not guaranteed.

- Administrative Obfuscation: His practice of handling export licenses in a way that masked the true exporter complicates efforts by the Republic of Cyprus today to trace and potentially reclaim objects based on historical export records.

The last point is of particular importance, in the following figure the entire license is shown of the previous receipt. This sale and its subsequent export was for a Mr. Beasly, yet the signature clearly says "Kolokasides". While not illegal, it is in the modern day highly problematic.

Ancient objects get passed from entity to entity either through sale, gift or inheritance. Being able to re-connect provenance is critical to separate looted or illegally exported objects from legitimate ones. If Mr. Beasly were to now contact the Cypriot Department of Antiquities, they would have no way of finding this export license. There is not a single trace of the purchaser on this license, with only vague descriptions of the objects contained within it. "One base ring juglet" could refer to any one of the many hundreds of examples exported from Cyprus.

Kolokasides was a product of his time, operating within a legal framework that, despite aiming for control, ultimately enabled the commodification and international dispersal of cultural heritage on a significant scale, often at the cost of scientific knowledge. His name, preserved in provenance records globally, serves as a reminder of this difficult period. The legacy is one of lost information, dispersed heritage, and ongoing challenges for researchers and heritage managers seeking to understand and safeguard Cyprus's rich past. The full story of P. Kolokasides may remain partially obscured, but his role in this complex history, and the problematic aspects of the system he navigated, warrant critical examination.